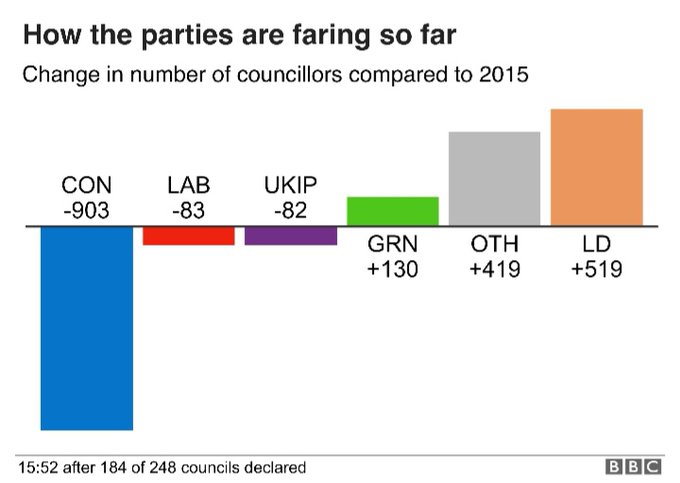

It’s only 4:30pm and only 202 of 259 councils have declared results, but patterns are already becoming apparent in these elections. It’s impossible to ignore the giant blue bar descending on the left of that results graph: the Conservatives are losing, and losing hard.

Theresa May, of course, still sees these results as a mandate to get on with Brexit. However, she is an increasingly lone figure. The big story of the night is that the Liberal Democrats are making a grand resurgence back onto the field of politics, justifying their continued existence and enabling 75 year old Vince Cable to step down in favour of a new generation – likely Jo Swinson, who has been his deputy both as Party Leader and previously as Business Secretary.

However, how warranted is this interpretation? It’s certainly reassuring for the Remain vote to see such positive support for clearly remain parties (the Lib Dems and the Greens) and significant hits to ambivalent or pro-Brexit parties (the Conservatives, Labour and UKIP), but there’s one significant bar which isn’t being paid enough attention: the grey bar of “other”. In 2018, Other and the Liberal Democrats had roughly the same proportion of the vote. Indeed, this has been the case since 2011, when the Liberal Democrats suffered historic losses. Before that time, the Liberal Democrats held a significantly higher proportion of the vote at between 25% and 26% of the vote.

The balance of these two groups suggests a mutual decline in trust of the two main parties whilst also indicating a difference of opinion in how that gap is best filled. There are two options if voters disagree with both standard parties: vote for an established political party which represents your values, or go for a grassroots approach by investing in individuals as Independents. There is a clear proportion of the population who, having lost faith in both major parties, have lost faith in the political system altogether. Since 2011, the proportion of those who believe in politics as we know it, and of those who don’t, has been roughly equal. We must be careful when celebrating a return to civilised politics. There are dissatisfied Leavers as well as dissatisfied Remainers. Until the concerns of both are met, the vote will likely continue to be split.

Also crucial are the hidden votes in this year’s council elections. There have been widespread reports of voters having to spoil their ballots after finding they had no pro-Remain candidate to vote for. The most common parties cited as intended preferences were the Lib Dems and the Greens, the two most clearly Remain parties. However, also hidden in the figures are Brexit Party and CHUK voters. The former is almost certainly much more significant than the latter, and also likely more well-hidden, given that CHUK have advised their supporters to vote Lib Dem or Green where possible.

It’s unlikely that Brexit Party voters would have voted Conservative or UKIP as both parties are distinct from what is essentially the Nigel Farage movement. Farage carries a cult of personality on his shoulders. As such, his voters place their trust very directly in him, his personality and his (as they see it) integrity, rather than the values he claims to represent. We will have to wait until the EU elections to see how UKIP fares against the fully-realised Brexit Party. Farage’s Brexit Party is a new iteration of his movement for a different political situation. We will only see the scale of its impact when it manifests on the electoral landscape.

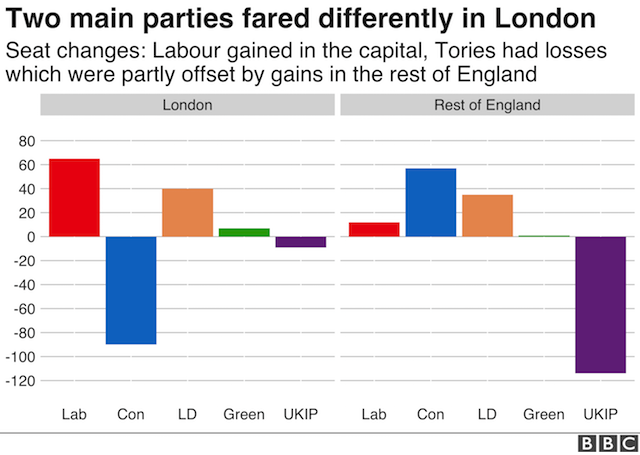

Perhaps the biggest story is the losses of the Conservatives in non-London areas. No elections were due in London this time, but it’s the non-London areas which counted. There, the Conservative losses have been significant, with 937 of 2620 councillors lost so far. In 2018, when local council elections were held both in London and in rural areas, losses sustained in the capital were bolstered by gains in the rest of England. Outside London was where the Conservatives could least stand to lose councillors.

It’s true that any party which has been in power for going on 9 years now is bound to be in severe decline. Parties rarely survive longer in power in British politics. Too much political baggage accumulates and the country typically clamours for a change of direction along with a much-needed injection of new ideas and new energy. The Conservatives should be losing in these elections. Similarly, a period of exile is common for parties who are punished for a perceived major error, as the Lib Dems were over tuition fees. They should be making gains.

However, combined with the wider Brexit crisis and the rising age of transition to Conservative support (now 51 years old), the Conservatives should be seriously considering bolstering their electoral viability and changing strategy if they are to survive, whether or not they continue to stay in power. Losses outside London are yet another nail in that electoral coffin. This is just as important as the rising age of transition and should be significantly concerning for the Conservatives in terms of continuing decline in their support.

Similarly, Labour should be making those gains from the Conservatives as the official party of Opposition. Yet by throwing their lot in with the Conservatives, both through talks and through announcing confirmation of their commitment to Leaving the EU with their ‘Alternative Plan’, they have effectively become the deputy government as far as the Brexit debate is concerned. Labour once took over as the second party of government from the Liberals, winning their first election in 1924. Labour still have the same proportion of the vote as the Conservatives and the Liberals are still far below where they should be, but the Lib Dems are making gains. The overall projected vote share of the two major parties has decreased, from 35% to to 28%. Like the Conservatives, Labour need to take action if they are to salvage their decline and continue to be the second party of British politics.

Whether or not these elections can be seen as a precursor, or indeed as a surprise at all, will only become clearer in comparison with the upcoming EU elections and, ultimately, with a new General Election. The apparent trends are largely in line with what could be expected from context: Conservative decline; Liberal gains; UKIP declines in preparation for an anticipated Brexit Party surge. However, it is the losses for Labour and the implications for broader Conservative decline from which we have the most to learn from these results.

One thought on “Understanding the Local Election Results”